Why diet is not just a personal choice

(Even though it feels like one)

*This article is also published in The Future is Vegan*

How many times have we caught up with our friends over lunch or dinner? “Long time no see, let’s catch up over dinner on Saturday!” A healthy and financially stable person usually eats about three to four times a day. Today, we don’t only eat to survive but also to socialise. Such a frequent and important activity condones a high level of autonomy for us.

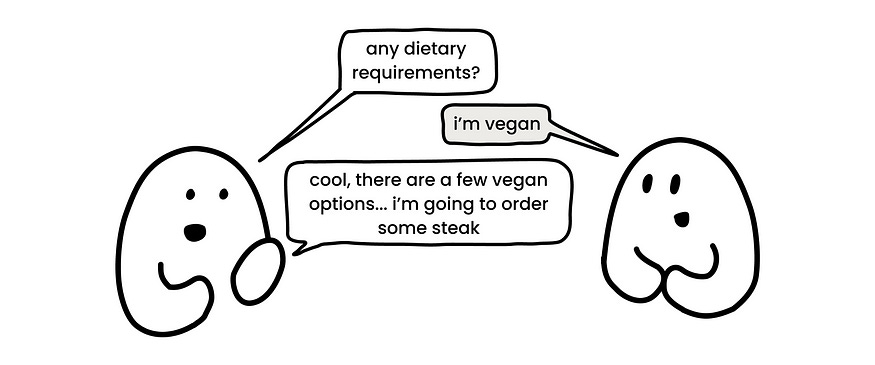

When we get together with friends over a meal, we’re usually respectful of one another’s dietary preferences, as long as we get to eat what we wish without feeling imposed upon — you do you.

We respect someone’s actions or beliefs as long as they don’t affect us. Fair play? Let’s dive a little deeper.

Moral relativism (“you do you”)

Let’s consider the idea of moral relativism, the idea that there is no universal set of moral principles. Moral relativism is widely practised in the world; it is the reason various cultures sometimes tend to have significant differences in what they consider right and wrong, despite co-existing with other cultures. Differences in moral standards are seen even amongst individuals, for example, between people with differing political affiliations, between vegans and non-vegans, and between racists and non-racists.

However, it seems as though we tend to exercise moral relativism (i.e. “you do you”) in certain situations but not in others. We are less likely to accept someone’s moral stance if, for example, they’re killing other people. We are more likely to accept someone’s moral stance if, for example, they eat (by effectively paying someone to kill) animals. Why the discrepancy when, in both situations, it is ultimately a personal choice and there is a living and sentient being’s welfare in question?

Legal vs. moral

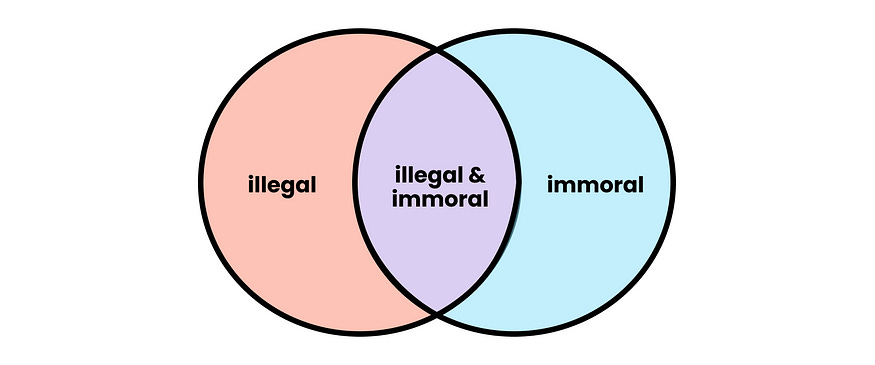

In the former instance (killing people), there are legal repercussions. In most places, it is legally wrong to kill a human being unless it’s done in self-defence. It’s safe to assume that in the majority of cases, legal representation of a moral stance depends on and to a considerable extent drives attitudes on the moral issue in question.

For example, slavery being illegal, most people also do not morally support slavery. While slavery-like practices, such as human trafficking and forced labour, still exist today, they are against the law and most people around the world are against such practices. The same stands for sexual harassment and rape; while they were legal many years ago, most countries have made these illegal now due to a large portion of their population being strongly against such forms of violence.

Unfortunately, there are no legal repercussions for slaughtering certain non-human animals for human consumption, even though there is no consent involved and these animals do not want to die. Not surprisingly, most people support this practice too. There are also distinctions in the law that protect certain species of non-human animals, like cats and dogs, but don’t protect farmed animals against the same or worse forms of cruelty. If we really think about it, these distinctions are entirely arbitrary because farmed animals have the same capacity to suffer and feel pain as companion animals. They ought to be given the same moral consideration and protection.

“Just because something is not illegal does not mean it is moral. Legality often lags behind morality; laws have changed over time to reflect the values of the majority of society.”

Laws tend to be viewed as a pillar of morality. However, legality does not equate to morality. Just because something is not illegal does not mean it is moral. Legality often lags behind morality; laws have changed over time to reflect the values of the majority of society. The majority of the human population still eats animals due to centuries of conditioning and normalisation of exploiting animals (excluding survival situations where killing and eating an animal is the only option), and as such, the law does not reflect this moral value.

Beyond personal preferences

While the mantra “you do you” often prevails in discussions about personal dietary choices, the impact of these decisions extends far beyond individual preferences. Using moral relativism to justify actions that harm sentient beings is problematic. Recognising the broader consequences of our dietary choices prompts a shift from mere personal autonomy to a shared responsibility for the well-being of other beings, and not just our own being. Perhaps it’s time to question the notion of diet being a purely personal and autonomous choice when that choice robs a sentient being of their autonomy.

Thanks for reading! That’s a great point about moral permissibility. I think it gets tricky in situations where non-vegans don’t see it as a moral conversation and therefore bring “personal choice” into it.

Cool article! I've come to understand the notion of a 'personal choice' just to refer to something that is morally permissible for one to do. i.e. it's a personal choice. Otherwise the term seems rather trivial in the context of moral conversation, i.e. someone would just be stating that it's a choice they happened to make (which leaves open the question of whether it was a good, bad, or non-moral choice).